Wednesday, February 24, 2021

The Mediterranean Diet: Your Complete How-To Guide

The Mediterranean diet even sounds good.

It conjures images of stucco villas perched over sparkling seas, where fresh sardines leap onto your plate, already golden, crispy, and dripping with olive oil.

And let’s not forget the vino.

But scientifically-speaking, the Mediterranean diet is also good for you.

That’s because it’s associated with a lowered risk of many diseases, plus a longer lifespan.

There’s a caveat, though: Maximizing these health benefits isn’t about just eating popular Mediterranean “superfoods.”

The real “secret” to the Mediterranean diet? Consistently eating a range of nutritious whole foods—and adopting certain lifestyle practices.

In this article, we’ll give you all the details. You’ll learn:

- How the Mediterranean diet was created (or rather, stumbled upon)

- The health benefits you can expect from the Mediterranean diet

- Why the Mediterranean diet isn’t for everyone

- Whether red wine lives up to the hype

- How to apply the Mediterranean “way of life” to yourself, or to the clients you coach

Hop on the gondola and let’s explore.

Mediterranean Diet Basics

Back in the 1950s, Ancel Keys, a scientist at the University of Minnesota, noticed something:

Poor, small towns in Italy hosted strikingly healthy citizens.

He attributed their robust health to their diet—largely composed of whole grains, legumes, fruit, and vegetables, moderate amounts of fish, and low amounts of dairy and meat.

Their primary fat source was olive oil, and they drank wine moderately.

These Mediterranean villagers also flavored their meals with an abundance of herbs, garlic, and onions.

Their food choices added up to a diet:

- Low in saturated fats, with almost zero trans fats

- Moderate to high in unsaturated fats

- Moderate in protein

- Rich in fiber and complex carbohydrates

- Rich in vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals

Italians weren’t the only people eating this way. Researchers documented similar eating patterns in Spain and Greece.

Over the decades since Keys’ original findings, the Mediterranean diet has been applied and studied in other contexts—like Canada, the US, India, and Western Europe. It still holds up.

So there is something special about a traditional Mediterranean eating style.

And at the same time…

It’s not just about the food.

In addition to having a distinct dietary pattern, “traditional” Mediterraneans also tend to practice specific cultural and lifestyle habits.

For example, they buy their foods locally, making multiple trips a week—often by foot—to local farm-sourced vendors.

They may also harvest produce from their own garden. This means that food is exceptionally fresh, and exercise is rolled into the act of procuring foods.

Mediterranean cooking and eating tends to be slow, social, and joyous.

Often, meals are eaten with family from multiple generations. It’s common for everyone to gather at Nonna’s every Sunday, where they’ll eat her handmade gnocchi with sauce made from her own garden tomatoes.

Compare that to how people frequently eat in modern Western culture.

Many of us are conditioned to quickly scarf down whatever’s in front of us. Often, that may be something highly-processed that’s easy to prep and clean up, such as a packaged burrito or a salad bowl of cereal.

Plus, it’s not a leap to imagine that breakfast, lunch, or dinner (or maybe all three!) are consumed in front of a device or steering wheel—perhaps while alone or barely speaking.

If really stressed and pressed, we might even eat over the sink.

That’s no way to enjoy a meal.

More important: If this describes your eating habits, you may be missing out on part of what makes the traditional Mediterranean lifestyle so notable.

That’s because:

- Eating locally is associated with better nutrition, less-processed food, obesity prevention, and lowered risk of diet-related chronic disease.1

- Eating communally is related to better nutrition, especially in children who eat with their families.2 In addition, those who eat socially often feel happier, are more trusting of others, are more involved in their local communities and have more social support.3,4

- Eating slowly is linked to a lowered risk of obesity, even when controlling for other lifestyle habits such as alcohol consumption, exercise, and smoking.5 And if you’re looking to lose weight, learning to eat slowly can help you moderate food consumption and feel more satisfied.6

- Eating home-cooked meals more often (at least five meals at home per week) is associated with eating more fruit and vegetables.7

In other words…

Getting all the benefits of a traditional Mediterranean diet isn’t just about what you eat. It’s also about where, why, and how you eat.

Eat more like a traditional Mediterranean, and you’ll probably experience some health benefits.

But live more like a traditional Mediterranean? That’s next-level stuff.

Mediterranean Diet Pros

The Mediterranean diet is one of the most robustly studied therapeutic diets.

But unlike many diets, it wasn’t developed based on a hypothesis of what should work. Nor did it become popular because an influencer “got great results on it.”

The Mediterranean diet rose to prominence based on what lots of real people were already eating and doing.

The original followers of the Mediterranean diet weren’t “on a diet” at all—they were just living their lives. That means it’s been shown to be a sustainable, long-term approach for a very large number of people.

Now let’s take a look at the specific health benefits it provides.

The Mediterranean diet may lower your risk of chronic diseases.

It’s associated with lowered incidences of:

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease

The Lyon Heart Health study, which involved 605 patients with heart disease, tested the Mediterranean diet against a control therapeutic diet. After four years, those on the Mediterranean diet had a 50-75 percent reduced risk of another heart attack.8

The Mediterranean dieters also consumed more fiber, vitamin C, and omega 3s, and less saturated fat and cholesterol than those on the control diet.

Diabetes

Diabetes

The Mediterranean diet is associated with improving blood sugar regulation, as well as a 19-23 percent reduced risk of future diabetes risk. So, adopting a Mediterranean diet may help prevent type 2 diabetes.9

For those with established diabetes, a lower carbohydrate version of the Mediterranean-style diet seems to help control blood sugar.

(To get a Mediterranean diet that’s customized for your goals and preferences, check out the Precision Nutrition Calculator.)

Angina

Angina

A Mediterranean diet rich in alpha-linoleic acid (plant-based omega-3s) and plant sterols—primarily from nuts, seeds, and plant oils—helps reduce the severity of angina.10,11

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease

In a study of 1188 healthy elderly Americans, those who adhered closely to a Mediterranean-style diet had a 32-40 percent reduced risk of Alzheimer’s.12

The risk of Alzheimer’s was reduced even further (67 percent less likely to develop the disease) with more exercise and a more consistent Mediterranean eating pattern.

Cancer

Cancer

The Mediterranean diet may contribute to a reduced risk of cancer, possibly due to a predominance of foods rich in antioxidants and fiber. And, according to some research, the closer people stick to the Mediterranean diet, the lower their likelihood of a cancer diagnosis.13,14,15

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction

Men who followed the Mediterranean diet for two years had fewer symptoms of erectile dysfunction (ED)—as well as improved blood vessel function and lower markers of inflammation—compared to those on a control diet.16

The Mediterranean diet may help reduce ED by reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome, a major risk factor for ED.17

In addition to (or perhaps because of) reducing the risk of many diseases, the Mediterranean diet is also associated with a longer lifespan.18

The Mediterranean diet isn’t about eliminating “bad foods.”

Instead, it’s about eating a delicious range of foods that most people enjoy—without prohibiting anything.

Think: “inclusion” not “avoidance.”

For example, sweets aren’t eaten regularly, but they’re not “forbidden” either. They’re just treats—to be enjoyed on occasion (and hopefully with lots of gusto and pleasure).

This means that the diet is practical, flexible, and psychologically, kind of freeing. Not surprisingly, research shows this kind of approach often leads to better results.19

And indeed: The Mediterranean diet appears to be one of the easier diets to stick to.

In a study of 250 people that compared long-term dietary adherence, 57 percent of people on the Mediterranean diet were still following it after a year, compared to 35 percent of people who tried the Paleo diet.20

Mediterranean Diet Cons

Most diets have some drawbacks, usually related to what they restrict. This often makes them psychologically or nutritionally challenging—or both.

Because the Mediterranean diet is inclusive of so many foods, it doesn’t provoke either of these challenges.

But there are other reasons why the Mediterranean diet may not be the “perfect” approach. (And to be clear: There is no perfect diet.)

Not everyone agrees on what the Mediterranean diet is.

Because the Mediterranean diet wasn’t purposely created by a group of doctors, dieticians, or scientists, it doesn’t come with strict rules. It’s more of a “pattern” of eating.

For example, if someone’s following a gluten-free diet or a vegan diet, you can assume that gluten-containing or animal foods are eliminated.

But with the Mediterranean diet, nothing’s really excluded.

Ultimately, there’s just a focus on particular foods—such as olive oil, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, and seafood.

For some, these fuzzy borders can make the Mediterranean diet seem more complicated than it is.

Case in point: If a person likes clearly-defined rules and precise meal plans, the Mediterranean diet might feel really challenging.

What makes the Mediterranean diet great can also make it hard.

Traditional Mediterraneans don’t tend to eat a lot of red meat (because the region lacks the land to raise cattle). To be clear, though, this isn’t an indictment of red meat.

It’s simply cause-and-effect: They eat fresh foods that are available locally, which we’d consider a “core principle” of the diet.

That might sound ideal, but it can be problematic for many people.

If fresh food is either inaccessible or unaffordable, following a “true” Mediterranean diet may not be practical (or possible). Same goes for someone who feels like they don’t have time or energy to prepare nutritious meals.

The Mediterranean diet may not be the best choice for weight loss (unless you combine it with other strategies).

People who start following a Mediterranean diet do typically lose weight.

This is interesting because:

Restriction—of food groups or calories in general—isn’t a central principle of the Mediterranean diet.

When people lose weight on the Mediterranean diet without attempting to modify portions, it’s probably due to something known as dietary displacement.

In other words, calorie-dense, highly-processed foods—for example, pastries, soda, and chips—are “crowded out” by lower-calorie, higher-nutrient whole foods such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and lean proteins.

While whole foods are hard to overeat, highly-processed foods are basically designed for overeating.

(Learn more: Manufactured deliciousness: Why you can’t stop overeating.)

So when switching to a more whole foods diet, you may eat fewer calories—without even trying to.

However, if you’re set on losing a specific amount of weight, you’re better off using an intentional strategy than relying on it happening by accident.

Our advice?

Combine the healthy variety of foods the diet promotes, as well as the lifestyle factors—like movement and mindful eating—with intentional portion regulation.

For portion recommendations to match your individual nutrient requirements and health goals, check out our Nutrition Calculator. (There’s even an option to tailor your recommendations to fit into a Mediterranean-style diet.)

Red wine: What’s the actual deal?

Is red wine good for you?

Meaning: If you’re not already drinking red wine, should you start?

As with most nutrition debates, it’s complicated.

The benefit of red wine potentially comes from its abundance of phenolic compounds, which are plant chemicals with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. (Note: These compounds are 10 times higher in red wines than in white or rosé wines.)

Moderate consumption of red wine is associated with lower blood pressure21, higher levels of “good” HDL cholesterol, lower levels of “bad” LDL cholesterol, lower blood sugar, and lower levels of inflammation. (Alcohol also acts as a blood thinner, which may be helpful for preventing clots.)22,23

For cardioprotective effects, international guidelines suggest limiting red wine to about 5 ounces (150 mL) a day. Drink more than that, and the health benefits fade. Higher alcohol consumption is associated with higher blood pressure, more inflammation, and worsened blood sugar regulation, not to mention an overall increased risk for many chronic diseases.24

The verdict?

If you delight in the occasional glass of red wine with dinner, you probably don’t need to stop.

However, if you’re a non-drinker, most health experts recommend that you don’t start.

Besides, there are less controversial foods that are even better sources of phenolic compounds, such as many culinary herbs and spices, teas, berries, and olives.25

(If only a cocktail of oregano, cloves, green tea, elderberries, and black olives were more appealing…)

For more on the pros and cons of alcohol consumption read: Would you be healthier if you quit drinking?

How to coach someone on the Mediterranean diet

If it’s not clear by now, here’s the beauty of the Mediterranean diet: It doesn’t require perfection.

What’s more, clients can start benefiting even if they don’t change what they eat right away.

Our approach: Have your client choose one practice at a time, and see how it works for them. As they successfully incorporate it into their life—give it a couple of weeks—they can choose another.

This helps ease them into it, and before they know it, they’re stacking several new practices that can drive meaningful change. Only it doesn’t feel daunting or difficult.

And that’s a powerful formula for change.

Here are the main tenets of the Mediterranean diet, which you can work on with clients one-by-one.

Savor and enjoy your food.

Help your clients eat more mindfully.

This means: Slow down. Look at the food; smell the food.

Chew carefully, paying attention to textures and flavors. Put your fork down between bites. Breathe.

Like any kind of practice, this isn’t all or nothing.

In fact, it’s quite hard for many people. So don’t expect hour-long meals right off the bat.

Most clients will benefit from adding just five minutes to their usual routine.

Even this little extra time can allow them to notice a little more, relax and de-stress a bit, and get more enjoyment from their eating experience.

(Read more: Try our 30-day slow eating challenge.)

Connect with loved ones.

While regularly eating with loved ones may not be possible for all clients, you can help them move towards more connection, however that looks in their life.

Encourage clients to invite friends over for a potluck, join a community gardening project, or visit their local farmers’ market to connect with farmers who grow and raise food locally.

Even if their household’s schedules are hairy and varied, suggest trying to schedule a weekly meal where everyone can eat together.

This isn’t just good for grownups, by the way.

Research shows that children who eat with family tend to eat more nutritiously2, and girls have a lower risk of developing an eating disorder.26

Plus, the benefits of eating together extend throughout life: Seniors who go from living and eating alone to dining communally in a nursing home or retirement community tend to eat better quality food, have more stable body weights, and have lower rates of depression.27

Move daily.

This can certainly include more conventional exercise like weight training, but it can also be: house work, walking a pet, running around with kids, using a treadmill desk, or just walking to the grocery store and back.

Here’s a practice we love: An Italian tradition called “la passeggiata.” This describes a leisurely after-dinner stroll through the neighborhood with family.

It’s a great way to combine activity, social connection, and mindfulness, which is probably why it’s thought to have significant health benefits.28

We also like intermittent workouts. These are 5- to 10-minute mini-workouts that clients can do throughout their day, without having to set aside 30 minutes or an hour for intentional exercise. (Learn more: How to do intermittent workouts.)

Eat what’s fresh and local(ish).

Mediterranean regions have access to specific fruits (like figs and grapes), vegetables (tomatoes and wild greens), and fats (olives, walnuts, and seafood).

Because of the region’s geography, red meat isn’t as common as chicken and seafood, which Mediterraneans can raise in a small backyard or fish from the nearby sea.

You and your clients might have different foods available.

Instead of getting stuck on specific Mediterranean foods, adopt the logic behind food choices.

Traditional Mediterraneans generally ate foods that were grown locally, and therefore were as fresh as possible. Those foods were also then mostly prepared at home.

The takeaway: Help clients get curious about the seasonal and local foods in their region. Then, help them build a repertoire of simple recipes that they can make from those foods.

The big benefit here: This automatically cuts out many of the energy-dense, ultra-processed foods that people often overconsume.

Emphasize plants, plant fats, and seafood.

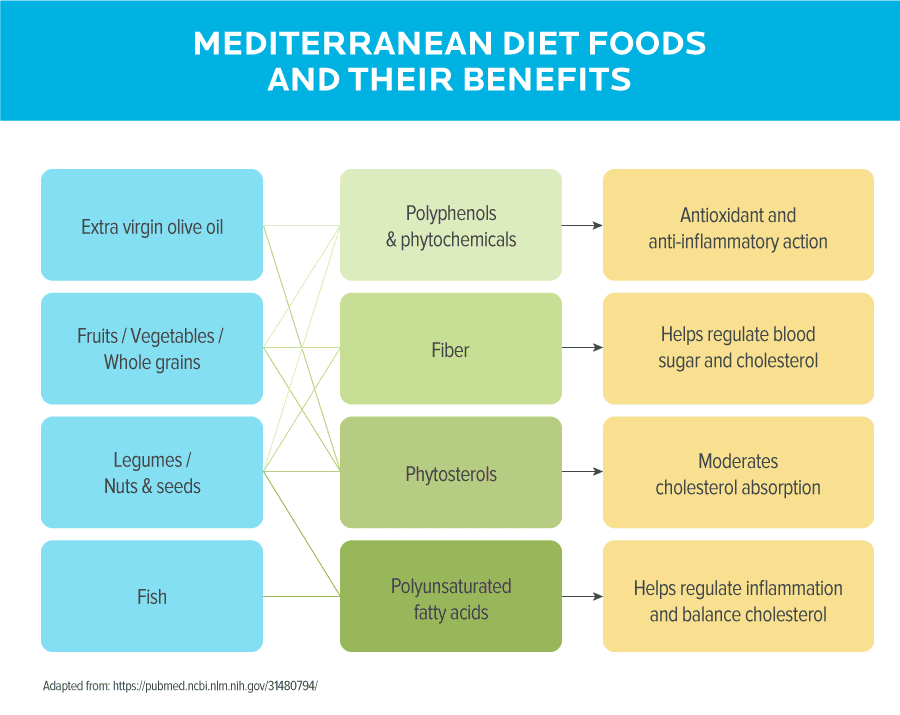

The Mediterranean diet probably works in part due to specific dietary patterns rather than individual foods.

These patterns include:

- Focusing on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains as the base of the diet

- Swapping out saturated fats (from fattier cuts of meat and high-fat dairy products) for more unsaturated fats (from nuts, seeds, and olives / olive oil)

- Including small, daily portions of dairy like yogurt and fresh or aged cheese

- Rotating protein sources, mainly from seafood, legumes, poultry, and eggs

- Replacing desserts with fruit

- Using generous amounts of natural flavor-enhancers, such as garlic, onions, and fresh and dried herbs

Giving clients this overview can be helpful, but asking them to make all these changes at once can be overwhelming.

Instead, turn these patterns into daily actions that clients can practice one at a time, until they’re ready to add more.

For example, they could choose any one of the actions below, and practice it for two weeks.

- Add 1-2 extra portions per day of fruit and vegetables to their diet

- Eat a serving of nuts and seeds a day, for a snack

- Include quality protein at every meal

- Switch your processed carb favorites to whole grains, beans, lentils, and starchy vegetables

- Swap treats and desserts for fresh fruit

- Moderate alcohol intake to one drink per day (or less)

Let’s say, for example, they want to swap dessert for fresh fruit.

Does this mean they have to give up cake? Absolutely not. What you’re looking for is progress.

For example: If they have dessert every day, could they trade that for fruit four or five days a week? Or if that feels too hard, three days? Or even just one day?

Don’t worry if it seems too easy. Easy is good because it allows them to experience success. They can build from there.

(Learn more about this coaching technique: The genius way to help clients change.)

Another approach? Have them look at their current dietary habits and get creative about “Mediterranean-izing” them. Here are a few examples:

| Currently eating… | Mediterranean version |

|---|---|

| Butter Bacon bits Cream cheese / mayonnaise Steak |

Olive oil Toasted nuts / seeds Avocado Salmon |

The Mediterranean Diet Food List

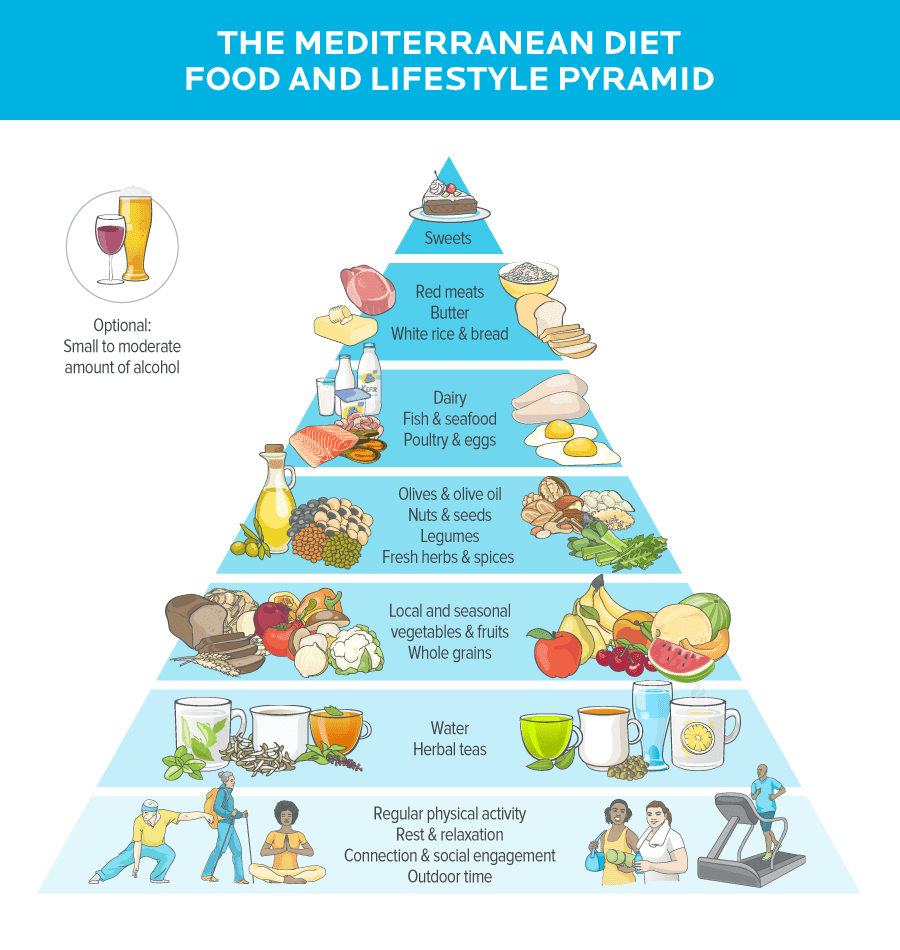

Traditionally, the Mediterranean plate includes:

- A high proportion of vegetables and fruits

- A high proportion of whole grains

- A moderate proportion of protein from seafood, legumes, poultry, eggs, and Greek yogurt

- A moderate proportion of fats from nuts, seeds, olives / olive oil, and fresh and aged cheeses

- A low proportion of animal-derived fats like lard and butter

- A low proportion of protein from red meat

- A very low proportion of sweets and desserts

For a complete guide, use our Mediterranean diet food list infographic to help yourself and your clients choose foods that are more Mediterranean-aligned.

As you use the list, please keep in mind: There is no one-size-fits-all Mediterranean diet.

Our list will help you focus on minimally-processed whole foods while also keeping your overall nutrient intake balanced.

If you’re a coach, you may have clients who follow different diets—and that’s okay. The important part: helping them stay successful on whatever diet (or no-diet) they choose.

Great nutrition coaches recognize that each client’s eating pattern can be individualized based on:

- What makes them feel best

- What supports their personal goals

- What’s realistic for them to follow

One tool that can help: Our Best Diet Quiz. It’s a quick and easy assessment that helps you figure out how well a diet is working for you (or your client).

And if you decide that the Mediterranean diet isn’t right for you?

That’s okay.

There are many other ways to eat—vegetarian, fully plant-based (a.k.a. vegan), Paleo, keto, carb cycling, reverse dieting—that can also help you reach your goals.

You can also check out the “anything” diet in the Precision Nutrition Macro Calculator. It allows you to create a free nutrition plan that’s personalized for your body, eating preferences, and goals. (Yes, you can eat “anything.”)

Because ultimately, it doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks is the “best diet.”

All that really matters: Finding what diet works best for YOU.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

- Martinez, Steve, Michael Hand, Michelle Da Pra, Susan Pollack, Katherine Ralston, Travis Smith, Stephen Vogel, et al. 2010. “Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues, ERR 97.” US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service 5. http://dx.doi.org/.

- Dallacker, M., R. Hertwig, and J. Mata. 2018. “The Frequency of Family Meals and Nutritional Health in Children: A Meta-Analysis.” Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 19 (5): 638–53.

- Herman, C. Peter, Janet Polivy, Patricia Pliner, and Lenny R. Vartanian. 2019. “Effects of Social Eating.” In Social Influences on Eating, edited by C. Peter Herman, Janet Polivy, Patricia Pliner, and Lenny R. Vartanian, 215–27. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. 2017. “Breaking Bread: The Functions of Social Eating.” Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 3 (3): 198–211.

- Tanihara, Shinichi, Takuya Imatoh, Motonobu Miyazaki, Akira Babazono, Yoshito Momose, Michie Baba, Yoko Uryu, and Hiroshi Une. 2011. “Retrospective Longitudinal Study on the Relationship between 8-Year Weight Change and Current Eating Speed.” Appetite 57 (1): 179–83.

- Spiegel, Theresa A., Thomas A. Wadden, and Gary D. Foster. 1991. “Objective Measurement of Eating Rate during Behavioral Treatment of Obesity.” Behavior Therapy 22 (1): 61–67.

- Mills, Susanna, Heather Brown, Wendy Wrieden, Martin White, and Jean Adams. 2017. “Frequency of Eating Home Cooked Meals and Potential Benefits for Diet and Health: Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Population-Based Cohort Study.” The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14 (1): 109.

- Kris-Etherton Penny, Eckel Robert H., Howard Barbara V., St. Jeor Sachiko, and Bazzarre Terry L. 2001. “Lyon Diet Heart Study.” Circulation 103 (13): 1823–25.

- Martín-Peláez, Sandra, Montse Fito, and Olga Castaner. 2020. “Mediterranean Diet Effects on Type 2 Diabetes Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A Review.” Nutrients 12 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082236.

- Estruch, Ramon, Miguel Angel Martínez-González, Dolores Corella, Jordi Salas-Salvadó, Valentina Ruiz-Gutiérrez, María Isabel Covas, Miguel Fiol, et al. 2006. “Effects of a Mediterranean-Style Diet on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Randomized Trial.” Annals of Internal Medicine 145 (1): 1–11.

- Singh, Ram B., Gal Dubnov, Mohammad A. Niaz, Saraswati Ghosh, Reema Singh, Shanti S. Rastogi, Orly Manor, Daniel Pella, and Elliot M. Berry. 2002. “Effect of an Indo-Mediterranean Diet on Progression of Coronary Artery Disease in High Risk Patients (Indo-Mediterranean Diet Heart Study): A Randomised Single-Blind Trial.” The Lancet 360 (9344): 1455–61.

- Scarmeas, Nikolaos, Jose A. Luchsinger, Nicole Schupf, Adam M. Brickman, Stephanie Cosentino, Ming X. Tang, and Yaakov Stern. 2009. “Physical Activity, Diet, and Risk of Alzheimer Disease.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 302 (6): 627–37.

- La Vecchia, Carlo. 2004. “Mediterranean Diet and Cancer.” Public Health Nutrition 7 (7): 965–68.

- Verberne, Lisa, Anna Bach-Faig, Genevieve Buckland, and Lluis Serra-Majem. 2010. “Association between the Mediterranean Diet and Cancer Risk: A Review of Observational Studies.” Nutrition and Cancer 62 (7): 860–70.

- Benetou, V., A. Trichopoulou, P. Orfanos, A. Naska, P. Lagiou, P. Boffetta, D. Trichopoulos, and Greek EPIC cohort. 2008. “Conformity to Traditional Mediterranean Diet and Cancer Incidence: The Greek EPIC Cohort.” British Journal of Cancer 99 (1): 191–95.

- Esposito, K., M. Ciotola, F. Giugliano, M. De Sio, G. Giugliano, M. D’armiento, and D. Giugliano. 2006. “Mediterranean Diet Improves Erectile Function in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome.” International Journal of Impotence Research 18 (4): 405–10.

- Beck, Leslie. n.d. “The Complete A-Z Nutrition Encyclopedia: A Guide to Natural Health: Managing Over 75 Health Concerns With Diet Vitamins Minerals Herbs: Beck, Leslie: 9780143169437: Books – Amazon.Ca.” Accessed January 26, 2021.

- Lasheras, C., S. Fernandez, and A. M. Patterson. 2000. “Mediterranean Diet and Age with Respect to Overall Survival in Institutionalized, Nonsmoking Elderly People.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71 (4): 987–92.

- Gibson, Alice A., and Amanda Sainsbury. 2017. “Strategies to Improve Adherence to Dietary Weight Loss Interventions in Research and Real-World Settings.” Behavioral Sciences 7 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030044.

- Jospe, Michelle R., Melyssa Roy, Rachel C. Brown, Jillian J. Haszard, Kim Meredith-Jones, Louise J. Fangupo, Hamish Osborne, Elizabeth A. Fleming, and Rachael W. Taylor. 2020. “Intermittent Fasting, Paleolithic, or Mediterranean Diets in the Real World: Exploratory Secondary Analyses of a Weight-Loss Trial That Included Choice of Diet and Exercise.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 111 (3): 503–14.

- Weaver, Samuel R., Catarina Rendeiro, Helen M. McGettrick, Andrew Philp, and Samuel J. E. Lucas. 2020. “Fine Wine or Sour Grapes? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Red Wine Polyphenols on Vascular Health.” European Journal of Nutrition, April.

- Agarwal, Dharam P. 2002. “Cardioprotective Effects of Light-Moderate Consumption of Alcohol: A Review of Putative Mechanisms.” Alcohol and Alcoholism 37 (5): 409–15.

- Ruf, J. C. 1999. “Wine and Polyphenols Related to Platelet Aggregation and Atherothrombosis.” Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research 25 (2-3): 125–31.

- Markoski, Melissa M., Juliano Garavaglia, Aline Oliveira, Jessica Olivaes, and Aline Marcadenti. 2016. “Molecular Properties of Red Wine Compounds and Cardiometabolic Benefits.” Nutrition and Metabolic Insights 9 (August): 51–57.

- Pérez-Jiménez, J., V. Neveu, F. Vos, and A. Scalbert. 2010. “Identification of the 100 Richest Dietary Sources of Polyphenols: An Application of the Phenol-Explorer Database.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 64 Suppl 3 (November): S112–20.

- Neumark-Sztainer, Dianne, Marla E. Eisenberg, Jayne A. Fulkerson, Mary Story, and Nicole I. Larson. 2008. “Family Meals and Disordered Eating in Adolescents: Longitudinal Findings from Project EAT.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 162 (1): 17–22.

- Kimura, Y., T. Wada, K. Okumiya, Y. Ishimoto, E. Fukutomi, Y. Kasahara, W. Chen, et al. 2012. “Eating Alone among Community-Dwelling Japanese Elderly: Association with Depression and Food Diversity.” The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 16 (8): 728–31.

- Egolf, B., J. Lasker, S. Wolf, and L. Potvin. 1992. “The Roseto Effect: A 50-Year Comparison of Mortality Rates.” American Journal of Public Health 82 (8): 1089–92.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

The post The Mediterranean Diet: Your Complete How-To Guide appeared first on Precision Nutrition.

from Blog – Precision Nutrition https://ift.tt/3sh0rrk

via IFTTT

No comments :

Post a Comment